DIATTO'S HISTORY

![]()

On 19 February 1819 King Vittorio Emanuele I proclaimed:

«... the city of Turin will be enlarged from the village of Po to the river

bank». The construction of piazza Vittorio - according to the wishes of Carlo

Felice - the

bridge and the Church of Gran Madre di Dio, inaugurated on 20 May 1831, gave a

new shape to the city, the fourth time the city had been enlarged.

On 19 February 1819 King Vittorio Emanuele I proclaimed:

«... the city of Turin will be enlarged from the village of Po to the river

bank». The construction of piazza Vittorio - according to the wishes of Carlo

Felice - the

bridge and the Church of Gran Madre di Dio, inaugurated on 20 May 1831, gave a

new shape to the city, the fourth time the city had been enlarged.

In 1835 a 30-year old wheelright by the name of Diatto,

from the nearby farming village of Carmagnola, settled in the city, leasing

from Count Francesco Gay a small strip of land on the right-hand bank of the

River Po, for the manufacture and repair of carriage wheels. This was the

beginning of what was to become a major auto manufacturer.

Vincenzo died, unmarried, on 10 August 1880, leaving his

property and assets to his mother, brothers and sisters. Four years later, on

14 September 1884, his brother Pietro died. For the sake of convenience the

manufacturing facilities were made over to the two remaining brothers.

On 3 February 1909, in order to build a new bridge over

the Po, to be named after King Umberto I, assassinated in Monza, the Turin City

Council requisitioned part of the Diatto property. Since 1899 Diatto had been

buying up land in the Crocetta area; in 1912 the company bought the factory and

land owned by auto manufacturer Itala, the new corporate headquarters in via

Rivalta 15, Orbassano.

The company existed independently for 83 years, but the

name Diatto continued to be used in the auto industry due to the work of

Giovanni Battista Diatto’s sons Vittorio and Pietro (Guglielmo’s grandsons),

who stipulated an agreement on 12 April 1905 between their company - Ingegneri

Vittorio e Pietro Diatto-Fonde-rie Officine Meccaniche Costruzioni in Ferro -

and the Société des Établissements Adolphe Clément-Automobiles Bayard based in

Levallois Perret (Paris), for the manufacture of French automobiles under

license.

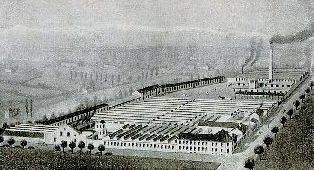

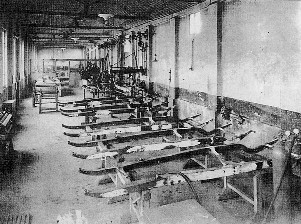

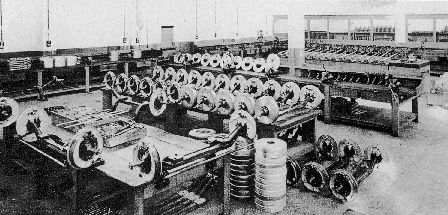

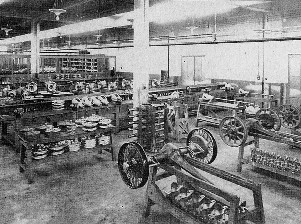

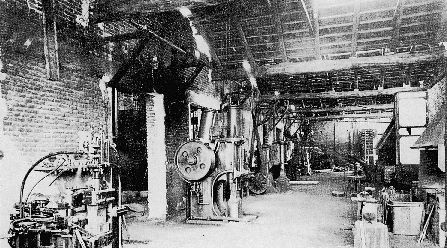

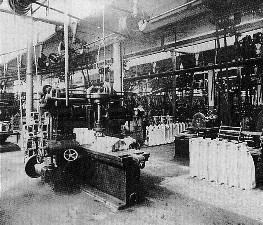

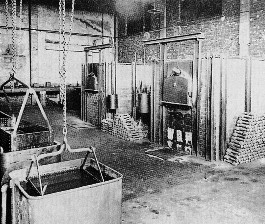

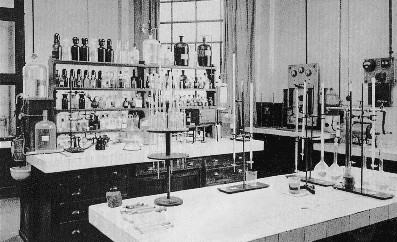

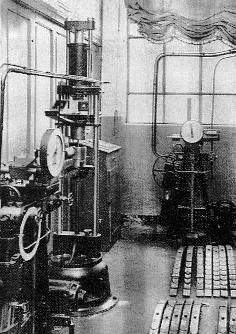

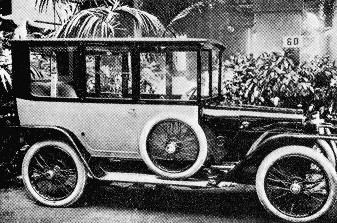

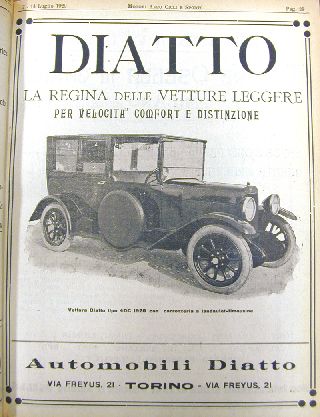

The new company was called Società Automobili Diatto-A. Clément with a share capital of Itl 1,500,000, of which Itl 450,000 was paid up, and duration until 30 September 1935. The company was based in Turin, with 25,000 square meters of facilities between via Fréjus, Cesana, Revello and Moretta: 90 HP of power was installed, supplied by 3 three-phase motors driving about 200 machine tools, for 500 workmen. Corporate headquarters was at via Fréjus 21.

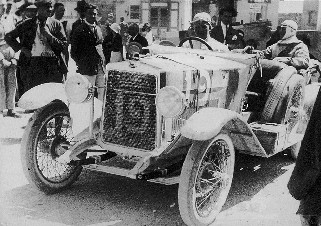

Italy was represented by an Itala driven by Prince

Scipione Borghese accompanied by the mechanic and co-driver Ettore Guizzardi,

and by the famous journalist Luigi Barzini, acting as correspondent for the Corriere

della Sera and Daily Telegraph. The Prince was a meticulous man; the car was

stripped down to remove anything not strictly necessary but still weighed in at

around 2 tons. The weight was useful on the many dirt roads along the route.

At 7.30 a.m. on 10 June 1907 Guizzardi turned the

crankshaft and started the engine. The race began at 8.00 a.m. The

first article written by Barzini was telegraphed from Hong Kong, after crossing

the Great Wall of China and the Gobi desert: it was the first telegram to be

sent from the Hong Kong office after 6 years of operation.

On 10 August, 60 days after starting off, the Itala

reached Paris after a journey of 10,000 miles from Peking, featuring the Gobi

desert, Baikal Lake, Omsk, the Urals, Novgorod, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Berlin,

Liege and finally Paris. This tough test for springs, suspension, the engine,

tyres and brakes, was a major success for the Italian auto industry.

Diatto took note and prepared a car for the St.

Petersburg-Moscow race scheduled to start on 18 May 1908. 28 cars took part,

but only 9 reached the destination. The Diatto (number 25) driven by Primaversi

came home sixth. These race experiences influenced production, with heavy-duty

vehicles equipped with excellent braking systems. One example was the 4,846 cc

25/35 HP produced in 1907, with chain transmission (conventional Cardan

transmission from 1909). Although much more expensive than previous models (Itl

16,500), this car was enormously successful and was produced until 1910. On 30

June 1909, Vittorio and Pietro Diatto bought out the shares of Adolphe Clément,

changing the company name to Fonderie Officine Fréjus.

All new cars would have the famous oval Diatto badge on

the radiator, a logo that was used unchanged until the factory closed and still

famous throughout the motor racing world.

(It should be remembered that, despite the similarity

with the Bugatti logo, the oval Diatto logo was used from 1909 onwards and was

submitted to the patents office on 5 June 1919, pre-dating both the invention

of the Bugatti logo in 1911 and the registration on 1st May 1925).

A few months after becoming a fully independent company,

the factory produced a new 4-cylinder 209 cc monoblock 15 HP engine, designed

entirely in-house. The engine was coupled to a 3-speed transmission plus

reverse.

A few months after becoming a fully independent company,

the factory produced a new 4-cylinder 209 cc monoblock 15 HP engine, designed

entirely in-house. The engine was coupled to a 3-speed transmission plus

reverse.

With the war in Libya, the Balkan conflict and the First

World War, the industrial revolution encouraged by Prime Minister Giolitti, was

given further impetus. The war required arms and vehicles. The first

reconnaissance planes and bombers were used in Libya. Machines became part of

everyday life, power and speed no longer being thought of as unnatural or

somehow devilish.

In mid-August 1905 Queen Margherita was the object of

this kind of superstition. Four shepherds in the mountains of the Aosta valley

saw her aboard the Sparviero, a convertible, followed by a second car, the

Allodola, with devilish rays from the front of the cars: they broke the

headlamps with stones and the car plummeted into a ditch, without falling

further. «It could have been a catastrophe» was the comment of Illustrazione

Italiana «but it was what we will come to call an accident». Margherita did not

move, just looked at the St. Christopher she kept with her at all times. On her

prompting, St. Christopher became the patron saint of motorists.

In 1908 the King’s car, on route from Racconigi to

Piacenza, took an unexpectedly tight corner and finished in a ditch; the

following year, near San Marino, perhaps after brake failure, 8 motorists from

Padova were killed; in 1910, on a French race track, the Turin racing driver

Giuppone, skidded off the track and was killed; three years later a powerful

car travelling near Savona collided with two oxen.

In 1908 the King’s car, on route from Racconigi to

Piacenza, took an unexpectedly tight corner and finished in a ditch; the

following year, near San Marino, perhaps after brake failure, 8 motorists from

Padova were killed; in 1910, on a French race track, the Turin racing driver

Giuppone, skidded off the track and was killed; three years later a powerful

car travelling near Savona collided with two oxen.

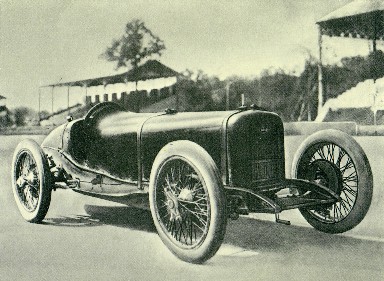

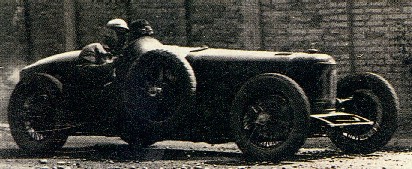

These accidents created a partially negative atmosphere

around the auto industry but did not prevent Diatto, in 1910, from arriving at

the Brooklands circuit in England with a highly aerodynamic racing car, powered

by a 15.9-litre aircraft engine - a clear indication of the ambitions of the auto

manufacturer. In 1911, Diatto began production of a new vehicle, the 16 HP

Unique Type with monoblock 2,212 cc engine and 3speed transmission.

In 1912 this model was transformed into a new 18 HP

Unique Type, now with 2,413 cc engine and 4-speed gearbox; until 1915 this

remained the standard car, with slight changes to front and rear width,

distance between wheels and overall weight.

Diatto was one of the leading manufacturers on racing

circuits throughout this period. On 21 June 1914, Eugenio Silvani won a 4-lap

(160-mile) race in Tuscany on the San Pietro track from

Sieve-Scarperia-Giogo-Fiorenzuola-Passo della Futa-San Pietro and back to

Sieve. The outbreak of the First World War in Italy, in May 1915, removes the

last few reservations about the use of powerful engines, now used in the war

effort.

Diatto was one of the leading manufacturers on racing

circuits throughout this period. On 21 June 1914, Eugenio Silvani won a 4-lap

(160-mile) race in Tuscany on the San Pietro track from

Sieve-Scarperia-Giogo-Fiorenzuola-Passo della Futa-San Pietro and back to

Sieve. The outbreak of the First World War in Italy, in May 1915, removes the

last few reservations about the use of powerful engines, now used in the war

effort.

In October 1911 and January 1912, the poet Gabriele

D’Annunzio had praised the war in Libya publishing “Canzoni delle gesta

d’oltremare” in the Corriere della Sera, and in Paris, Marinetti’s “Guerra

igiene del mondo” (War, hygiene for the world) praised «... the formidable

symphonies of shrapnel and crazed sculptures created by our artillery in the

enemy camp». To create these “crazed sculptures” and to fly over Trento and

Vienna to drop propaganda leaflets, industry was required to produce aircraft

and support vehicles.

The war helped convince Italy that automobiles were here

to stay; this was strengthened by the mountain terrain and shape of the

peninsula which made railway building more difficult than in other countries.

Road building went ahead quickly. In 1910 62 private companies managed 1,875

miles of road; in 1912 this had gone up to 5,235 miles, and on 30 June 1914 it

was 7,344. Immediately after the armistice a further 200 licenses were given

for the construction of 3,750 more miles, with petrol stations selling

subsidized petrol below the market price. In 1924 Italy had a total of 33,000

miles of main and B roads, with GT routes and seasonal services for spa towns

and health resorts.

In 1915 Diatto began production of light trucks,

converting its standard frames to military use. These trucks proved to be strong

and reliable. During the same year, a new body shop was inaugurated in via

Moretta, Turin, and two new factories were acquired from John Newton in Turin

and from Scacchi in Chivasso.

In 1916 Enzo Ferrari and his brother Alfredo bought a red

Diatto which he described in his memoires: «Alfredo volunteered for the war; it

was the time Red Cross volunteers were taken if they had some kind of vehicle.

The red 4-cylinder Diatto Torpedo we had bought went with him, to transport the

wounded from the front to hospitals».

The war changed the working class. In July 1915 Critica

Sociale (Social Criticism), the socialist magazine founded and directed by

Filippo Turati, denounced the psychological damage of workmen producing

entirely for destructive purposes for many years. «What will the consequences

be» he wondered, «for the economy and finances after the War?». The War was

gearing the mechanical engineering industry up to huge profits based on

estimates for old, badly organized artillery workshops which had now been

converted into standard production lines, with a fraction of the cost.

Management chose this moment to challenge the proletarian movement.

Fiat, one of the largest producers of war equipment,

returned profits of 80% of turnover, leading to a sevenfold increase in share

capital and a tenfold increase in the number of employees.

Fiat, one of the largest producers of war equipment,

returned profits of 80% of turnover, leading to a sevenfold increase in share

capital and a tenfold increase in the number of employees.

At the end of the War, Diatto underwent a new change,

becoming Società Anonima Fonderie Officine Fréjus Automobili Diatto (a

joint-stock company) in 1918. The following year, its name was changed again,

to Società Anonima Automobili Diatto, with a new organisation and new corporate

headquarters in Rome (only in 1920), closer to the source of a credit of Itl 6

million (the equivalent today of Itl 300 bn) owed by the State for war

equipment manufactured by Gnome et Rhône; this debt was never settled, creating

negative repercussions throughout industry.

European factories, hit by the unexpectedly difficult

conversion to a peace time footing, also faced a chronic shortage of money and

government policy which continued to regard automobiles as useless - perhaps

even damaging - luxuries, with narrow roads and asphalt surfaces suited to no

more than 20-30 mph, partly enhanced by the aristocratic image of the

automobile, the favourite playthings of Dukes, Princes, and members of the

Royal Family.

In 1928 the German auto manufacturer Ferdinand Porsche

spoke in less than friendly terms of aristocratics: «they talk about democracy

but they want luxury cars».

Three years were to pass before the first Volkswagen, the

“dream car” as it was called in September 1931 by Porsche, and a further three

years went by before the first Balilla. Three years may not be much, but they

were enough to finally rid the world of the idea of motor cars as playthings

and to create the utility car for the masses.

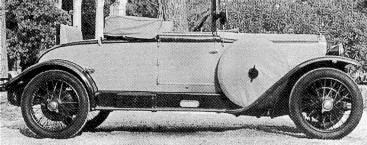

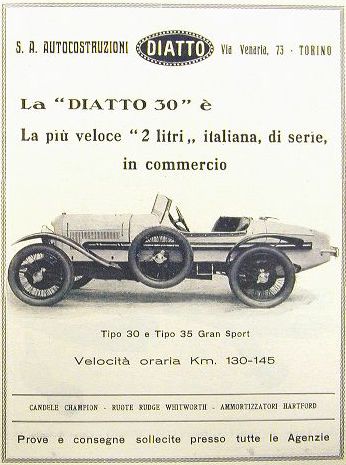

Diatto had just been waiting for the moment. In 1919 it

had produced three new car based on this concept: the 30 Type, on license from

Bugatti, with a 1,452 cc engine with valves and overhead camshaft, the 10 HP

Type with 1,018 cc engine and 3-speed gearbox with reverse, an early attempt to

produce a utility car, and the model 25 HP 4 DA e 4 DC produced in the Gnome et

Rhône factories, with 2,724 cc engine, produced until 1922 with a slight change

to the distance between the wheels.

Diatto had just been waiting for the moment. In 1919 it

had produced three new car based on this concept: the 30 Type, on license from

Bugatti, with a 1,452 cc engine with valves and overhead camshaft, the 10 HP

Type with 1,018 cc engine and 3-speed gearbox with reverse, an early attempt to

produce a utility car, and the model 25 HP 4 DA e 4 DC produced in the Gnome et

Rhône factories, with 2,724 cc engine, produced until 1922 with a slight change

to the distance between the wheels.

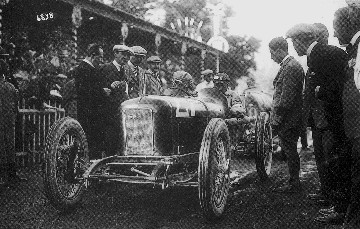

On 13 June 1920 a 6-lap race was held at the Mugello, in Tuscany, covering a total of 245 miles. 24 cars started the race; 5 finished. Augusto Tarabusi came second in a Diatto, with average speed of close to 40 mph, behind Giuseppe Campari, driving an Alfa Romeo. On 20 October the 11th Targa Florio race was held on the same track as the year before: 4 laps of the medium circuit of Madonie, 270 miles; Peter de Paolo and Peyron took part with their Diatto.

The situation was extremely serious: «Anyone at that

time», wrote the historian Morandi «who looked towards the Giovi pass, down the

valley towards Polcevera and further afield, Voltri and Sestri, would have seen

the red flags of the proletariat on the rooftops of factories. The same could

be said for Lecco, seen from Resegone, and Greco milanese, towards Mirafiori,

and in Biella and Brescia». The Prime Minister Giolitti waited and the

occupation of the factories burnt out on its own.

The situation was extremely serious: «Anyone at that

time», wrote the historian Morandi «who looked towards the Giovi pass, down the

valley towards Polcevera and further afield, Voltri and Sestri, would have seen

the red flags of the proletariat on the rooftops of factories. The same could

be said for Lecco, seen from Resegone, and Greco milanese, towards Mirafiori,

and in Biella and Brescia». The Prime Minister Giolitti waited and the

occupation of the factories burnt out on its own.

In 1921 the 4 DS, a modified version of the 4 DC, with

sports car performance and a top speed of over 90 mph, continued the company’s

racing interests. In 1921 Diatto decided to move corporate headquarters back to

Turin; the company also dedicated more attention to motor racing and set up its

own racing team. Share capital was increased to Itl 10,000,000, a huge figure

for the time, enabling Diatto to acquire a number of new short-term projects.

In 1922, Giuseppe Coda became Technical Director, after winding up his own

business, Veltro Società Automobili, after only a few months. He brought Diatto

the company’s idea for a new 2-litre engine, used for the Diatto 20 Type.

Together with the 20 S Type, this car was enormously successful on race tracks,

winning with champions such as Tazio Nuvolari, Antonio Ascari, Diego De

Sterlich, Emilio Materassi, Baroness Avanzo, Alfieri and Ernesto Maserati,

Gastone Brilli Peri, Giulio Aymini, Tarabusi, Ghia, Cesare Schieppati and

others.

The engine was slightly under 2 litres (1,995 cc), with 4

cylinders in a single block of cast iron with inserted head housing three

supports for the camshaft controlling the interchangeable valves by rocker

arms. The engine was silenced by equalisers on the camshaft, controlled by a

vertical shaft with helical gears, also controlling the water pump, magnet,

cooling fan and dynamo. The oil pump was fitted to the gear shaft and provided

oil under pressure. A high voltage magnet was used for ignition, with manual

control on the steering wheel.

The carburettor was automatic, with pedal or manual

control. Cooling was by water pump with radiator fan. The clutch was dry and

had only one disc, with a series of springs on the disc thrust device.

The four-speed gearbox had a trains balladeurs reverse gear.

A shaft transmission was used, with single universal joint and rear torque with

spiral Grearson teeth. The back end was in stamped steel. Braking was on all

four wheels, with the handbrake applied to the rear wheels or the gearbox

pulley. The frame was in C type 3 mm steel profile with rigid axis suspension

with half-elliptic spring.

The four-speed gearbox had a trains balladeurs reverse gear.

A shaft transmission was used, with single universal joint and rear torque with

spiral Grearson teeth. The back end was in stamped steel. Braking was on all

four wheels, with the handbrake applied to the rear wheels or the gearbox

pulley. The frame was in C type 3 mm steel profile with rigid axis suspension

with half-elliptic spring.

The Diatto 20, designed by Engineer Coda, was presented

at the 1922 Milan Exhibition just before beginning close co-operation with the

Maserati brothers, test drivers of the legendary 20 S.

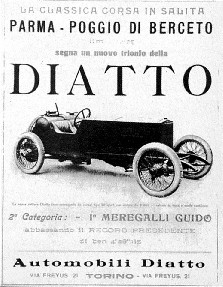

To get the car ready for Monza, Alfieri and Ernesto

Maserati moved to Turin. The 20 S was a modern, reliable and particularly;

driven by Meregalli, it was placed high up the field at the 13th Targa Florio

on 2 April 1922, winning the Parma-Poggio di Berceto on 14 May. Two Diatto 20 S

started the Italian Grand Prix in 1922. Meregalli was a frequent winner of the

tough Garda race, first with the standard 20 and then with the customised 20 S.

Alfieri Maserati won the Autumn Grand Prix in Monza with a 3-litre car.

In August 1923 the Alpine Cup hosted the writer and

journalist Arnaldo Fraccaroli who later published his memoir of the event,

co-authored with Sonzogno, a literary event which helped to popularise motor

racing, just as Luigi Barzini had done with his coverage of the 1907

Peking-Paris rally. Fraccaroli’s diary focuses less on speed than on endurance.

The mountain route included many places made famous or infamous by the War:

Saga, Caporetto, Tomino, the Isonzo river, the Carso in Istria; people from

Fiume waved, the Croatians did not wave. Drivers started out at around 4.00

a.m. and covered a distance of over 300 miles a day, in the heat and dust, up

to a height of around 8,000 feet. In Tione they received a bunch of flowers,

Italian flag and a plaque reading «for the courageous drivers on behalf of the

most patriotic valley in the Trentino». 44 drivers started the rally, with only

24 finishing. Diatto was represented by no less than 4 competitors, each of

whom obtained a good final placing.

The cylinder head was made of aluminium, with inserted

steel caps. The cylinder block, in aluminium, had screwed-in steel liners. The

connecting rods were tubular, with two overhead camshafts controlled by

cylindrical gears. The first tests were carried out with atmospheric feed and

two or four bronze Zenith carburettors, of 16 diameter. The engine weighed 156

kg (about 343 lb.). The engine was fitted to a 20 S Type frame and won the

Parma-Poggio di Berceto with Alfieri Maserati. Subsequently a Roots compressor

was fitted with two pressurized Memini carburettors downstream of the

compressor. A special mix of fuel, with Avio petrol and a small quantity of

benzol, was used to deliver close to 150 HP. At the same time the company was

developing the 1,995 cc 30 Type, with strong 4-cylinder engine, overhead

camshaft, valves and axles, delivering 52 HP and a top speed of over 70 mph.

The car was produced successfully until 1927, when it was replaced with the 26 Type.

At the 24-hour Le Mans in 1925, Diatto entered four cars,

two 25 Type and two 30 Type, winning the 2litre category with the Garcia-Botta

team, which also qualified for the prestigious Rudge Whitworth Cup (a 2-yearly

event). The 20 S driven by François Lecot won at Limonest. On 6 September 1925,

Diatto debuted with the 8-cylinder engine was driven by the impetuous Tuscan

Emilio Materassi who died three years later on the same Monza circuit, driving

a Talbot. 27 spectators were also killed in the most serious accident ever at

Monza. The new Diatto Grand Prix had a successful debut in terms of speed and

agility but failed on reliability, forcing Materassi out of the race, probably

due to the lack of time to properly test and fine-tune the engine.

At the 24-hour Le Mans in 1925, Diatto entered four cars,

two 25 Type and two 30 Type, winning the 2litre category with the Garcia-Botta

team, which also qualified for the prestigious Rudge Whitworth Cup (a 2-yearly

event). The 20 S driven by François Lecot won at Limonest. On 6 September 1925,

Diatto debuted with the 8-cylinder engine was driven by the impetuous Tuscan

Emilio Materassi who died three years later on the same Monza circuit, driving

a Talbot. 27 spectators were also killed in the most serious accident ever at

Monza. The new Diatto Grand Prix had a successful debut in terms of speed and

agility but failed on reliability, forcing Materassi out of the race, probably

due to the lack of time to properly test and fine-tune the engine.

The huge development cost of the car and its failure to

clinch a top place led managers at Diatto into a period of rethinking,

strengthened by the financial problems of the Musso brothers - new and

important partners at Diatto and their textile businesses.

The work force continued to hope and produced a new

model, the 35 Type, quite similar to the 25 Type, both with a 4-cylinder 2,952

cc engine with valves and axles on overhead camshafts, the former producing 75

HP and a top speed of 85 mph, the latter 70 HP and a top speed of nearly 80

mph.

On 21 September 1926 Giulio Aymini won the

Susa-Moncenisio with an 20 S, establish a new record for the class. In 1927 a

Diatto 30 came first in the 2,000 cc class and sixth overall at the Brooklands

6-hour race. In 1927, two experimental cars were prepared for the Mille Miglia,

with 2-litre 8-cylinder engines and compressor, producing 160 HP and a top

speed of over 135 mph! The Mille Miglia was the showcase the Fascist regime

intended to use to attract world attention to Italy.

On 21 September 1926 Giulio Aymini won the

Susa-Moncenisio with an 20 S, establish a new record for the class. In 1927 a

Diatto 30 came first in the 2,000 cc class and sixth overall at the Brooklands

6-hour race. In 1927, two experimental cars were prepared for the Mille Miglia,

with 2-litre 8-cylinder engines and compressor, producing 160 HP and a top

speed of over 135 mph! The Mille Miglia was the showcase the Fascist regime

intended to use to attract world attention to Italy.

As Gioventù Fascista (Fascist Youth) wrote: «... the

roads have been so well restored by Fascism, that it is now possible to drive

through half Italy and back in one stage, at an average speed of 110 kph (68.75

mph)». The same writer added: «... in Italy the discipline brought by Fascism

is so deeply rooted that 1,700 km of roads are open to traffic, day and night,

in cities and the countryside, so that there are hundreds of speedy vehicles on

the road at one time and no accidents occur». Hence «... Fascist Italy is a

breeding ground of energy, science, engineering, work, organisation, sport».

The Mille Miglia became one of the world’s foremost sporting events until the

tragic accident which killed Alfonso De Portago in 1957, the last year of the

race.

In 1927, Diatto took part with four 4-overhead valve and

two experimental 8-cylinder engines. In the same year the company launched the

new 2,632 cc 26 Type, producing 70 HP and a top speed of 87.5 mph. This was the

last mass production car manufactured by Diatto, which hit a new financial

crisis and went into voluntary receivership in 1931.

The first half of 1929 was more generous with good news,

at least seemingly: in February a new agreement was made between the Italian

state and the Roman Catholic Church, a victory for Mussolini; the agreement was

ratified by a form of referendum on 24 March. Tight monetary controls, as

announced by Benito Mussolini in Pesaro on 18 August 1926, were relaxed, only

to run into the Wall Street crash in October, the Great Depression and

consequent world recession. Credit protection was granted to Diatto on 29

October 1931; the following year, Carlino Sasso, the company’s Technical Director,

took over the business, rescuing it by good management and the focussing of

activities on spare parts for Diatto cars no longer in production, and the

manufacture of generating sets, compressors, pumps and pneumatic drills.

Mass production was beginning to rule the world, and cars

were becoming the opium of the masses at a time of worldwide recession and

sinister political developments in Europe. In 1930 Italo Balbo took 12

mass-produced hydroplanes over 6,000 miles from Orbetello to Rio de Janeiro.

Mass production was beginning to rule the world, and cars

were becoming the opium of the masses at a time of worldwide recession and

sinister political developments in Europe. In 1930 Italo Balbo took 12

mass-produced hydroplanes over 6,000 miles from Orbetello to Rio de Janeiro.

Cinemas became a popular form of entertainment. People

went on holiday in huge numbers, trains became a common sight; in January 1930

Prince Umberto married Maria Josè and the event was followed by Italy’s press

for the first time; on 24 April Galeazzo Ciano married Mussolini’s daughter

Edda, and a whole generation of women with the same name was born.

Diatto had ten relatively prosperous years in spare part and component manufacture while some gentlemen drivers continued to race, confident that spare parts would always be available. This was followed by the years of the war.